- Home

- Amy Sparling

The Truth of Letting Go Page 2

The Truth of Letting Go Read online

Page 2

Dad reaches for another slice of pizza, his arm barely missing my drink. I’d almost forgotten he was even here because he’s been so quiet. Where Mom is strict and perfunctory, Dad is laid back and relaxed. He even has a tattoo of a dog sunbathing on a beach towel permanently placed on his left calf. Mom goes to these training sessions every so often, but she’s never taken Dad with her before. He’s always been the chaperone staying home with us girls to make sure everything stays in order. Mom leaves a strict schedule and list of rules that we abide by while she’s gone, but as the years have changed us from little kids to almost-adults, Dad slacks up on the rules. But we’re seventeen now, and I guess age comes with slightly more freedom.

Mom says, “I will leave my car for you to use in emergency situations only. I have written down the mileage and left you with a full tank. I don’t expect you’ll need it for anything close to a full tank, understand?”

Okay, maybe freedom wasn’t the right word to use.

I nod. “No driving anywhere for any reason other than certain death. Got it.”

“If it’s certain death, you should probably call 9-1-1,” Dad says.

Mom ignores my sarcasm. “There’s cereal or toast and eggs for breakfast, and I’ve laid out plans for two meals a day for the next nine days. You’ll find them listed on the calendar.” She hooks her thumb toward the kitchen.

An entire wall of our kitchen is covered in chalkboard paint, organized into sections that dictate the comings and goings of our lives like a train schedule at Grand Central Station. Except, unlike a train terminal, we never get to leave the house when the parents are gone. Sure enough, the first week of June is filled out with lunch and dinner, along with notes like in freezer, thaw in the morning and bake at 350 for 45 mins.

Mom’s voice pulls my attention away from the board and back to the table. “Cece, your meds are refilled. Lilah, UPS should be delivering two packages for me this week, so make sure you check the front door. Curfew is nine instead of ten since no adults are home this week, but honestly girls, just stay home, okay? The less I have to worry about, the better.”

Mom takes a second to look both of us in the eyes, locking eye contact for exactly three seconds each. “You don’t need to go anywhere. All the food you need is here. If you must go out, make it brief and send me a text when you leave and when you get home. Got it?”

“Yes, Aunt Carol.” Cece dunks her pizza crust into a container of ranch sauce. I know she’s sick of dealing with my mother’s insane house rules. Living here is a chore for her, but like me, she has no other choice. All my life Mom has been heavy handed with the overbearing parenting, but after Thomas died, it only got worse. It’s probably the reason I haven’t had a boyfriend in so long. No one wants to date the girl who has to text her mom before and after she does anything.

Mom glances toward the chalkboard wall and frowns. “Unfortunately, this means we’ll have to reschedule the visit to your old house, sweetheart.”

Alarmed, I look over at my cousin. I’d almost forgotten the first week of summer was supposed to be reserved for cleaning out Cece’s old house before my parents put it on the market. After five years of keeping my aunt and uncle’s house the same as the day they unexpectedly left it, we now need the money for therapy and Cece’s future college expenses. Most of Cece and Thomas’ stuff had been taken out and moved in here, but the rest of her old life remains in their red brick home on the outskirts of town.

Cece’s face falls. She stares at her half-eaten slice of pizza and then shrugs. “No big deal.”

Dad clears his throat. It’s that classic change-the-subject thing he does. “Nine days is a long time to be bored at home. I think the girls could have a friend over if they want. Kit is trustworthy.” Mom’s eyes flash in his direction and he turns his palms up. “Just a friend, and maybe for an hour or two. That would be fine.”

Her lips press together. I know she won’t argue with her husband in front of us because one time years ago, the therapist told her they need to be a united front when dealing with us kids. Sometimes I think Dad waits to disagree with her until we’re around because he knows she won’t object.

Finally, she looks at me. “One friend at a time. One platonic friend. Text me when they arrive and when they leave.”

“Guess I can’t have anyone over,” Cece says, dabbing her mouth with a paper towel. “None of my friends are platonic.”

Mom sighs.

Dad stifles a laugh.

I just roll my eyes and reach for more pizza. Cece is always saying off the wall shit like that. She is bold and fearless. Except when she’s not. I think we’d all agree that sarcastic joking Cece is the best version of my cousin. The alternative is scary as hell. It’s the reason we’re not even friends anymore, which is saying a lot because the girl on the other side of this table used to be my best friend in the world.

The other side of Cece’s mental illness is a dark cloud that pulls all of the happiness from the room. And once it rises, we never know when it’ll go away. All we can do is hold on tight, maintain order, and wait for her to come back to us.

I pretend to be asleep when Mom pushes open my door a crack and whispers my name. She waits a beat and I focus my breathing to seem natural—long and slow breaths. REM sleep and all that. Mom is smart enough to know if I’m faking.

Finally, she whispers, “Goodbye, honey. I love you.”

My door softly clicks closed. I hear her walk down to Cece’s room where she probably whispers the same thing before padding back up the hallway and into the living room.

I exhale and open my eyes, staring at the glow-in-the-dark star stickers on my ceiling. They are a decade old and still glow like crazy every time I turn off the lights. In Cece’s old house, she has the same set of stickers, but hers are all over her walls, not the ceiling. Grandma gave them to us for Christmas one year and we put them up in each other’s rooms together. Back then, when her parents were alive and she was just my chubby cousin with no problems, we got along better. But there’s a big difference between seven-year-olds and teenagers. Now she’s a stranger to me. I see her every day, but I don’t get her at all.

I take a deep breath and roll over to my side, anxious to fall back asleep. It’s four in the morning on the first full day of summer break and I get to sleep as late as I want. For once in my life there will be no parentals banging on my door telling me to get up and find something productive to do with my day.

Only now I’m feeling like shit for ignoring my mom. I know it’s a crap thing to do because I should get up and hug my parents goodbye and tell them to have a safe trip. But I pretended to sleep to avoid having a laundry list of rules and expectations dished out so early in the morning. I already know them all by heart, but it doesn’t stop Mom from reciting them every time she leaves as if I’m some bad kid. As if I’ve ever broken any of her rules.

But I should have sucked it up, sat up in bed and told her I loved her too.

Five years ago, Cece’s parents went out for a date night and died a few minutes later, before they’d even arrived at the restaurant. Eighteen wheeler with a drunk driver at the helm. In their little smart car, they had no chance.

I bolt out of bed and run to my window. “Mom!”

The taillights of Dad’s truck cast a red shadow over the bushes near our mailbox. I watch them for a few seconds but then they’re gone. Guilt nags at me, and I go back to my bed and grab my phone and text my parents that I love them and I’m sorry I missed them.

Mom texts back right away. Love you too, sweetheart. Remember to follow the meal chart and don’t leave the house if you don’t have to! 9pm curfew! xoxo

I roll my eyes and drop back into bed. I’m not a scientist or anything, but it might be physically impossible for my mother to say something nice without adding a reminder to it. Rules and order, that is my life.

I really think she’s freaking out for nothing. Cece and I are almost legal adults. According to the state of Texas, we�

�re old enough to commit a crime and be tried as adults. Yet we can’t leave the house without texting my mother before and after an excursion? Cece hasn’t had a bad episode in months. It seems like the doctors finally got her under a cocktail of prescription drugs that do the trick. For a while there, she and I were bickering and arguing constantly. But now she just keeps to herself, so I do the same.

My cousin and I aren’t the little kids we used to be. We’re not friends anymore. I’m not sure what we are, not since she started having episodes and I had to step up and fill the shoes of caretaker when my mom isn’t around. I think she maybe resents me for it, but I resent her, too.

There was a time where Mom wasn’t obsessively controlling with every little thing in my life. Cece is the reason my mom is so dutifully mechanical about rules and structure. She’s the reason my life is one planned week after another, filled with constant text message check ins. Graduation is only a year away, and then I will be free, living alone at a college as far away as I can get.

I close my eyes and start to drift off again, only to be startled awake by a swift knock at my door. Cece is a professional knocker. She knocks with force and precision like I’m a lowly factory worker and she’s my boss. I nearly jump out of my skin when the sound bangs through my room and then I pull the pillow over my head and yell, “What?”

“Can I come in?”

“If it makes you stop knocking.”

I don’t take the pillow off my face until I feel her weight sink down at the foot of my bed. Cece’s hair is still in that long side braid, although now it’s messy from sleeping on it. She wears a set of matching thermal Christmas pajamas. Right in the middle of June. I know they’re just pajamas, but my holiday themed clothing items stay tucked away until it’s the appropriate holiday. I can already hear Mom’s voice in my head now. “Cece, dear, why would you wear something that’s so out of season?”

Mom always asks questions like that, an insult in the form of a genuinely concerned question.

I rub my forehead with my thumb and forefinger. “What’s going on?”

Her eyes are bright even in the dim light of my bedroom. Her round cheeks widen as she grins at me. “Aunt Carol and Uncle Kenneth are gone.”

“I heard.”

She scoots back a few inches on my bed, making the mattress wobble under her weight. “We should go to my house today.”

I yawn. “What?”

“My old house.”

I sit up on my elbows, blinking away the last bits of sleep from my subconscious. Cece’s brows crinkle as she watches me, doing that weird thing where I guess she’s trying to figure out what I’ll say before I say it. I roll my eyes. “Mom said we’ll start cleaning out your old house when they get back.”

“I don’t want to clean it out today. I just want to go visit.”

“Why?”

We haven’t been there in years. I remember my dad making two trips with a rented box van to pick up Cece and Thomas’ things from their bedrooms when they moved in with us. Cece shared my room and Thomas got the guest bedroom. A few weeks after Thomas was pronounced dead, Cece took over all of his things, making them her own. Mom once told me when we were alone that the therapist didn’t think it would be healthy to let Cece go back to the home that holds so many painful memories for her. Mom’s already freaked out about the four of us going to clean it out and have a garage sale. I know for a fact she wouldn’t want us to go alone.

I meet her gaze, and something guilty swells up in my gut. Maybe it’s from letting her ride the school bus yesterday instead of calling her over. “I don’t think that’s—”

“—A good idea,” Cece says, finishing my sentence. She heaves a sigh. “You always say that, Lilah. But what you don’t get is that I came in here and I sat down and I said ‘I want to go to my old house’. I did not say, ‘Do you think it’s a good idea?’” She holds her hands up, fingers splayed, and shakes them in frustration. “You’re always doing that to me.”

I start to say something, but I’ve got nothing. She’s right. But it’s my job to keep her calm and keep her at home. Deflect all of her terrible ideas the second she gets them. “How about we head to the donut place at the end of the road?” I say. Deflect. “They have the best coffee and it’s only like a mile of driving so Mom can’t bitch about us taking the car.”

Cece flattens her lips. They’re pale pink and always look like she’s wearing lip gloss, even though she rarely does. “I just want to see my house by myself. Before Aunt Carol comes with me and ruins the whole experience with her stupid psycho-babble.”

I can’t help but smile. “Let’s hold hands and talk about our feelings,” I say in my mom’s pretend soothing voice.

“Cece, what is something positive you can gain from this painful experience?” she says, also mocking Mom’s voice.

She grins and I start laughing.

“I love Aunt Carol, but damn,” Cece says, shaking her head. “Sometimes I think she’s more screwed in the head than I am.”

My smile softens and I look down at my comforter, purple and teal and in the pattern Cece helped me pick out years ago on one of her good days. I know where she’s coming from, and I know how frustrating it can be to be around my mother. I don’t even have to deal with a mental illness like Cece does so all my experiences are easier than hers.

“Fine,” I say, gazing across the room. In all my years on this planet, this one will be marked forever as the first time I went against my mother’s strict rules. “We’ll go.”

Cece squeals and clasps her hands together in front of her chest. I notice every one of her fingernails is pained a different color. “Thank you,” she says, biting on her lower lip. “I won’t—you won’t regret this.”

“It’s fine,” I say as a nervous twinge pierces my heart. This is so not a good idea. “But we’re waiting until the sun comes up.”

It was Halloween night and we were eight years old. My parents had dressed up as Hogwarts students and went to a party at the fire chief’s vacation home. It was an Adults Only party which made no sense to me at all, because Halloween was specifically a holiday for kids. At least it was in my mind. But they had Adult Stuff to do and I wasn’t allowed, so I stayed at my aunt and uncle’s house instead.

Cece’s parents were occasional foster parents, usually for babies or toddlers who were temporarily taken away from their real parents. None of the kids ever stayed over that long, but that Halloween night, there was a sadness in the air. Cece told me it was because this newborn boy they’d fostered for two weeks was taken back to their real family that morning. My aunt had grown a little too fond of him and was sad to see him go. All night I could tell something was a little off, but Aunt Summer was the kind of loving parent who would do anything to make us happy, no matter what she was feeling inside.

Cece and I dressed as M&Ms candies—she was blue and I was red—and those foam circles were just one cute getup in a long-standing tradition of matching costumes. Thomas never wanted to join in with us because our ideas were too girly and didn’t contain enough fake muscles for his liking. He was Batman that year because he’d discovered that costumes with masks gave him more confidence. While I’d known him my whole life and the birthmark on his temple was never something I thought about, it bothered him more than we knew.

Aunt Summer took us around the block to go trick-or-treating, but not many people were handing out candy, so instead, she packed us up in her SUV and took us to the nice neighborhood on the other side of town. Our bags were overflowing with sugary goodness by the time we finished, and Aunt Summer was in a really great mood. Halloween was one of those days that you looked forward to every year, spent weeks planning your costumes, and then suddenly before you realized it, the night was over.

We returned to Cece’s house to find that someone had taken the trick part of trick-or-treat literally. Aunt Summer’s mailbox was blown up. It turned out that some teenage punks had driven down the street putting M80 firecr

ackers into everyone’s mailbox.

In the morning, while my parents were sleeping off a hangover at home, I’d woken up in Cece’s bedroom to the sound of my uncle cursing in the driveway. As valiant as his attempts to make a new mailbox were, the thing wouldn’t stand up straight in the hole he’d shoved it into. Aunt Summer said he needed to fill the base with concrete, but he didn’t feel like it. When he finally relented and followed her advice, the wooden pole had slipped at an angle and froze like that in the hardened concrete.

The tires of Mom’s Malibu crunch over months of fallen pine needles and dead leaves that cover the driveway of Cece’s old house. The brand new real estate sign in the front yard is a contrast to the overgrown grass and faded paint on the house. The for sale part of the sign is covered with a white plastic rectangle that says COMING SOON. The moment we pass the crooked mailbox, nostalgia hits me hard, wrapping around my heart and squeezing as I pull to a stop and park the car.

Cece’s house sits at the end of the road, nestled between miles of trees and sloping hills on the outskirts of Telico. The grey shingled roof has black streaks running down it from age, but the red bricks and navy blue shutters are just how I remember them. Cece doesn’t say a word as we step out of the car. The smell of pine trees and the sound of birds singing in the distance bring me back to my childhood, playing in this front yard with my cousins, back when there were two of them. Back when you figured your parents would live forever and no one would ever go crazy.

Cece walks toward the garage on the right side of the house. I stand here, gazing up at the clouds, feeling like I’ve stepped out of a dream or a memory and that this isn’t reality at all. It’s too weird to be real. The last time I was here, I was thirteen years old and Mom was frantically rooting through Aunt Summer’s jewelry box, looking for the perfect necklace to bury her in. She was furious that the funeral home people had dolled her up with too much makeup and she wanted to bury her sister with something that felt more like her style.

Bella and the One Who Got Away

Bella and the One Who Got Away Bella and the New Guy (Love on the Track Book 1)

Bella and the New Guy (Love on the Track Book 1) Captivating Clay (Team Loco #3)

Captivating Clay (Team Loco #3) Believe in Spring (Jett Series Book 8)

Believe in Spring (Jett Series Book 8) Alluring Aiden (Team Loco Book 2)

Alluring Aiden (Team Loco Book 2) The Right Move (Mable Falls Book 1)

The Right Move (Mable Falls Book 1) Saving Hadley (Boys of Summer)

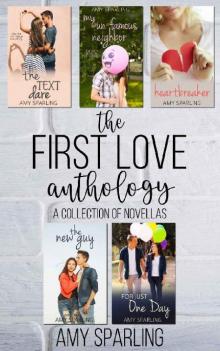

Saving Hadley (Boys of Summer) The First Love Anthology: A collection of novellas

The First Love Anthology: A collection of novellas Jayda’s Christmas Wish

Jayda’s Christmas Wish Deadbeat

Deadbeat In Every Way

In Every Way Winter Whirlwind

Winter Whirlwind Summer Together (Summer #2)

Summer Together (Summer #2) The Garden

The Garden Bella and the Happily Ever After

Bella and the Happily Ever After Spring Unleashed (The Summer Unplugged Series)

Spring Unleashed (The Summer Unplugged Series) Christmas with You (The Summer Series Book 6)

Christmas with You (The Summer Series Book 6) My Un-Famous Neighbor: A First Love Novella (First Love Shorts Book 2)

My Un-Famous Neighbor: A First Love Novella (First Love Shorts Book 2) Summer Unplugged

Summer Unplugged Bella and the Summer Fling

Bella and the Summer Fling The Truth of Letting Go

The Truth of Letting Go The Text Dare

The Text Dare The Wrong Goodbye

The Wrong Goodbye Lana's Ex Prom Date

Lana's Ex Prom Date Unplugged Summer: A special edition of Summer Unplugged

Unplugged Summer: A special edition of Summer Unplugged The Right Move

The Right Move The New Guy

The New Guy The Wrong Goodbye (Mable Falls Book 2)

The Wrong Goodbye (Mable Falls Book 2) Believe in Fall (Jett Series Book 6)

Believe in Fall (Jett Series Book 6) Believe in Winter (Jett Series Book 7)

Believe in Winter (Jett Series Book 7) Finding Mary Jane

Finding Mary Jane The Immortal Mark

The Immortal Mark Believe in Us (Jett #2)

Believe in Us (Jett #2) The Immortal Bond (The Immortal Mark Book 3)

The Immortal Bond (The Immortal Mark Book 3) Autumn Adventure (Summer Unplugged #6)

Autumn Adventure (Summer Unplugged #6) Ella's Stormy Summer Break (Ella and Ethan Book 2)

Ella's Stormy Summer Break (Ella and Ethan Book 2) Believe in Forever (Jett Series Book 3)

Believe in Forever (Jett Series Book 3) The Immortal Truth (The Immortal Mark Book 2)

The Immortal Truth (The Immortal Mark Book 2) Believe in Me (Jett #1)

Believe in Me (Jett #1) Believe in Love

Believe in Love Ella's Twisted Senior Year

Ella's Twisted Senior Year In Plain Sight

In Plain Sight Summer Apart

Summer Apart Heartbreaker (First Love Shorts Book 3)

Heartbreaker (First Love Shorts Book 3) Summer Forever

Summer Forever Phantom Summer

Phantom Summer Meeting Mary Jane

Meeting Mary Jane In This Moment (In Plain Sight Book 3)

In This Moment (In Plain Sight Book 3) Natalie and the Nerd

Natalie and the Nerd Taming Zach

Taming Zach Believe in Spring

Believe in Spring Autumn Awakening

Autumn Awakening Autumn Unlocked (Summer Unplugged)

Autumn Unlocked (Summer Unplugged) The Text Dare: A First Love Novella (First Love Shorts Book 1)

The Text Dare: A First Love Novella (First Love Shorts Book 1) Taming Zach (Team Loco Book 1)

Taming Zach (Team Loco Book 1) The Girl with my Heart (Summer Unplugged #8)

The Girl with my Heart (Summer Unplugged #8)